James Merle Weaver 1937-2020

Among the tragic and continuing worldwide death toll, the Covid-19 pandemic has devastated the world of classical music. Live performances continue to be cancelled, through the summer and, already, into the fall season. Coronavirus is costing musicians not only their livelihoods, but in some cases their lives.

A towering figure in the history of Washington’s classical music scene, James Merle Weaver, 82, died one month ago today of complications from Covid-19. He had recently moved to Rochester, N.Y.

Weaver came to Washington in 1966, to take a position at the Smithsonian, overseeing the collection of musical instruments held by the National Museum of History and Technology. He helped lead the Smithsonian’s musical activities for nearly forty years, and his list of accomplishments is staggering. His tireless efforts included not only historical keyboard music, a primary focus following his performance studies with Gustav Leonhardt in Amsterdam, but an eclectic range of interests including jazz and folk music.

Teaching and performing on keyboard instruments were an important part of Weaver’s life, and his generosity to students stood out. Harpsichordist Mitzi Meyerson, who now teaches in Berlin, described how Weaver watched out for her when she studied with him at Oberlin’s Baroque Performance Institute one summer.

“I was extremely young and desperately poor, and I didn’t have any money for food,” she said. “One day Jim approached me and pressed ten dollars into my hand, telling me to buy some food.

“I was embarrassed but grateful. When I asked how I should pay it back, he said I should forget about that, and just pay it forward.” Meyerson has done the same since her first job came along. “The first student who needed it got $100 for food and I regularly cooked for him,” she says. “This is a duty and a privilege, and I learned it from Jim.”

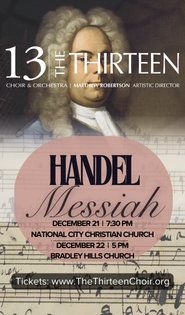

Seeking to give voice to the historic collection he expanded at the Smithsonian, Weaver sponsored performances on the instruments. He helped form the Smithsonian Chamber Players, securing private funding that continues today. Among many other achievements, Weaver led the first American performance of Handel’s Messiah on period instruments, recorded in 1981. He also gave work to a number of specialists in maintaining and making historical instruments.

Thomas and Barbara Wolf, the celebrated historical instrument builders in Virginia, recalled Weaver’s encouragement as they launched their workshop in the mid-1970s. “Jim lived out in Potomac then,” Barbara said. “And there was an old dairy barn that was next to his house.” At the time they were working out of their basement on Capitol Hill. “Jim offered us the barn, if we wanted to use it. So we were literally cheek by jowl there for a couple of years.”

“He ordered our first fortepiano,” Barbara also recollected. “Actually he and I owned that piano together for a while because he could only scour up so much money. But it was because of Jim insisting that it happened, because he wanted to have something that this new Smithsonian ensemble could use so they could move beyond harpsichord literature. We were never planning to do that.”

Peggy Dowd, a colleague at the Smithsonian in the late 1960s and 1970s, remembers that he used to joke that at that time making music in the museum was “like mixing a bowl of disciplined spaghetti” or “nailing jelly to the wall.” As she explained it drily, “People forget that the Smithsonian is a federal bureaucracy.”

Jay Scott Odell, a musical instrument conservator, said that Weaver somehow figured out how to get along well with everybody. “On the institutional side of the Smithsonian,” he remembered, “there’s a lot of jockeying for position, wrangling for pieces of the budget.” Weaver, it seemed, “could talk people into doing things they didn’t really want to do. By the time things happened, everyone was pleased with the result.”

The founding violinist in Weaver’s Smithsonian ensembles, Marilyn McDonald also recalled his art of persuasion. She was once driving with Weaver in his huge, antique Citroën, a car built before the Second World War, somewhere in downtown Washington when a police officer pulled them over. “Everyone was always looking at this car,” she said with a laugh. “Unfortunately we were going the wrong way down a one-way street. But we didn’t have to pay a ticket because Jim was very good at speaking to people, including policemen.”

Over the years Weaver brought many leading early music ensembles from Europe, making the Smithsonian “an epicenter for the historically informed performance practice movement,” as Eastman School of Music professor Nathan Laube recently put it. Among those artists were cellist Anner Bylsma, recorder player Frans Brüggen, and keyboard players Gustav Leonhardt, Jörg Demus, Paul Badura-Skoda, Christopher Hogwood, Alan Curtis, and Albert Fuller. Ensembles included Concentus Musicus Wien, the Kuijken Quartet, and the Early Music Consort of London.

“Washington certainly wasn’t a hotbed of early music activity in the 70s,” as Barbara Wolf put it. Weaver used his position to bring “the best people, the soloists and smaller ensembles from Europe. All those people, when they were touring every couple years, he made sure they came to the museum and that people were exposed to their performances.”

How could Weaver have achieved so much as a curator and concert presenter, all while continuing to work as a choir director and freelance keyboard player on the side? In most cases, it was sheer force of will. Marilyn McDonald also recalled one of the first major performances she did with him, at an outdoor summer festival playing Bach’s Sonata for Violin and Clavier in G Major. “The humidity in the summer is very difficult for gut strings,” she remembered.

“This was my first experience with having a string break when I was about to go out on stage,” she reminisced. “I just burst into tears.” For Weaver, though, there was never a question of stopping the performance. “He was very supportive,” she continued, “but he got me out on that stage. He was sympathetic, but you knew that the show must go on.”

McDonald also recalled commuting into town with Weaver from his home in Rockville, not in the big Citroën but in a beat-up Volkswagen Bug. “It had a hole in the floor, so that you could see the road passing underneath you,” she said laughing. “I remember the day we abandoned it on 14th and Constitution, where it caught on fire. I had a lot of fun with Jim. He just had a wonderful attitude about life. He was enthused about so many things, and I think that’s why he could also work at so many things. I don’t think he considered them jobs.”

Although he was officially retired, Weaver had never slowed down, taking on the leadership of the Organ Historical Society and other projects. Last year, Weaver and his partner, Samuel Baker, left Washington and moved to Rochester, N.Y. Within a short time, Weaver was responsible for a concert series there, at the Memorial Art Gallery.

Lisa Goode Crawford, a keyboard player who had taught alongside Weaver in the summers at Oberlin, reconnected with him when she began teaching in Rochester after he had relocated there. “He wanted to do a house concert that would combine baroque dance and harpsichord music,” she said, laughing.

“I was not sure about this concert, but Jim had this way of being unbelievably persuasive. He wasn’t going to let go. He made that happen.”

Posted May 16, 2020 at 7:19 pm by Howard Bass

Thanks for this wonderful tribute to Jim. I met him in the early 1970s and when he found out that I played guitar and lute he invited me to do weekly demonstrations in the museum’s Hall of Musical Instruments. Soon he was getting me involved in any number of other playing opportunities, and eventually he got me a full-time position as a program producer. Meeting Jim quite literally changed my life’s path and I will always be grateful beyond words for all that he did for me. Of course, that was Jim–he had a generous heart, and I was not the only beneficiary. May he rest in peace, and may his memory be a blessing.

Posted May 17, 2020 at 3:57 pm by Sheila Wing

What wonderful memories of Jim. I knew he was an amazing human, just had no idea how amazing and wonderful.

Thank you for sharing this beautiful history.