Performances

NSO celebrates America as the Kennedy Center’s closing looms on the horizon

As July 4 approaches, presenters and ensembles around the federal city […]

Exquisite moments from Beilman and Osborne at Library of Congress

Composers in the romantic period embraced the new capabilities of the […]

Friday the 13th brings good luck with Voyager Ensemble’s bracing program

Arnold Schoenberg may be the most famously triskaidekaphobic composer, but George […]

Music is the food of love in Opera Lafayette’s intimate Valentine’s Day program

Opera Lafayette is striking out in new directions. During the first […]

Vocal Arts presents the noteworthy local debut of a gifted French tenor

Last month, Vocal Arts DC became the latest presenter to move […]

Articles

Independence must be restored to the Kennedy Center in order to save it

When President Trump conducted a partisan takeover of the Kennedy Center […]

Top Ten Performances of 2025

1. Chamber music for strings and piano. Wu Han/Chamber Music Society […]

Overnight

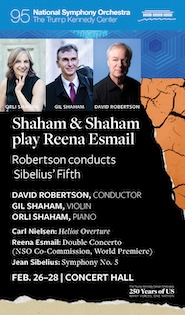

Sibelius takes flight under Robertson, while double concerto premiere lands with a thud

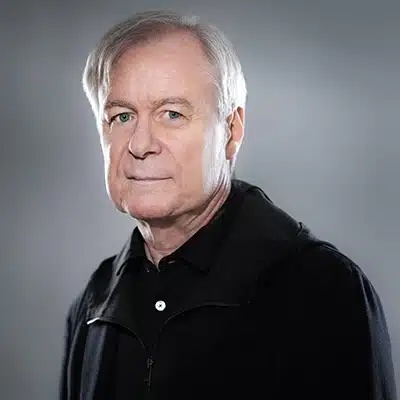

David Robertson conducted the National Symphony Orchestra Thursday night at the Kennedy Center.

Trust David Robertson to handle a world premiere. The American conductor, former music director of the Ensemble Intercontemporain in Paris, knows his way around modern scores of all stripes. In his last appearance with the National Symphony Orchestra, in 2022, he brilliantly led a recent piece by Steven Mackey. The centerpiece of this week’s program, heard Thursday evening in the Kennedy Center Concert Hall, was a world premiere.

Sadly, the Double Concerto of Reena Esmail did not live up to expectations. The Chicago-born composer is a rising star, having been awarded a handful of significant composer residencies this decade, most recently with the Marlboro Music Festival last summer. Like much of her work, the new piece reflected her Indian-American heritage and the Hindustani musical traditions of northern India, which she studied on a Fulbright-Nehru Scholarship.

Esmail built the concerto’s three movements on Hindustani classical raags, which are indicated in the score. Neither solo part, conceived for and debuted by violinist Gil Shaham and his younger sister, pianist Orli Shaham, held particular melodic interest. The piano part mostly outlined these melodic areas in arpeggiated clusters or repeated chords, while the violin part was often covered entirely, either set in its low register or doubled by the violin section. (Orli Shaham is also the wife of David Robertson.)

Gil Shaham and Orli Shaham were soloists in the world premiere of Reena Esmail’s Double Concerto Thursday night.

Furthermore, the three movements covered mostly the same stylistic territory, albeit with changes of melodic content and shifts in tempo. Impressionist tableaus, recalling models like Debussy’s evocations of Asian music, were succeeded by more cinematic writing, but the handling of the orchestra felt largely unvaried and lacking in color. Some hackneyed techniques, like the overused bell tree and other metallic percussion, cloyed more than augmented.

Gil Shaham’s dulcet top register proved an asset in the middle movement, in some more soloistic writing, including a brief section accompanied solely by piano. Esmail bumped the tempo up in the third and final movement, adding some dramatic glissandi for the piano, but the harmonic and melodic vocabulary never really deepened. Polite applause ended without an encore from the soloists.

The highlight of the evening turned out to be a subtly colored rendition of Sibelius’s Fifth Symphony. Robertson’s tempo choices all fit perfectly together, right from the valiant horn calls that opened the first movement. The strings sections’ oscillating motifs gradually added tension, which Robertson allowed to develop organically as the piece accelerated. Blooming forth from a heart-shaking crescendo, the musicians shifted gears almost imperceptibly as Sibelius transformed the movement into a whirling scherzo.

Robertson did not allow any time for applause, launching quickly into the second movement. Here and elsewhere, Robertson’s ear for control and balance brought out glistening textures, often with the violin section held back in velvety softness to allow other sounds to emerge. The music seemed to strain upward, partly due to Sibelius’s insistence on ascending leading tones repeatedly resolved throughout the movement.

Most remarkable was the third movement, where Robertson’s ideal tempo choice obviated any need for adjustment between the skittering fast music and the soaring longer notes of the swan theme. The horns did not dominate, receding in sound to allow space for the elegant melody in the woodwinds instead. With the same care for crafting sound from the softest beginnings, the swan theme moved through the other sections of the orchestra, gaining strength and leading to the symphony’s enigmatic conclusion, a series of staccato chords separated by long silences.

The pairing of this symphony with Carl Nielsen’s Helios Overture recalled a 2024 program from the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra with the same combination. Whether under-rehearsed or just not in the wheelhouse of either conductor or musicians, the Nielsen piece felt the least unified and polished. A serene opening depicted the sun rising over the Aegean Sea, but the faster parts that followed, especially the fugal section in the strings, did not cohere with the same natural ease heard in the Sibelius.

The program will be repeated 11:30 a.m. Friday and 8 p.m. Saturday. kennedy-center.org

Calendar

February 27

Washington Bach Consort

James O’Donnell, organist

Bach: Clavierübung III […]

News

Trump plans to shutter Kennedy Center for two years, causing upheaval for NSO, others

In a surprise announcement Sunday evening, President Trump declared that he […]

Washington Classical Review wants you!

Washington Classical Review is looking for concert reviewers in the DC […]