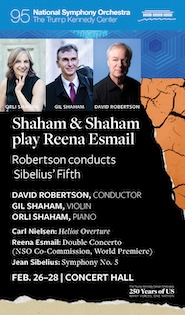

Sprites, fairies, and a cellist’s debut in NSO’s compelling Russian-French program

Vasily Petrenko conducted the National Symphony Orchestra Thursday night at the Kennedy Center. Photo: CF Wesenberg

Vasily Petrenko has returned to the podium of the National Symphony Orchestra, conducting another Russian-plus program Thursday night. Music director of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra since 2021, the conductor suspended all engagements in his native Russia following that country’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Yet as he told the audience in the Kennedy Center Concert Hall, “While politics has its twists and turns, music always unites us as humans.”

Anatoli Lyadov’s Kikimora, a compact tone poem about a malevolent female spirit from Russian folklore, opened in a gloomy mist. The back desks of the cello and double-bass sections rumbled a series of long notes establishing the key of E minor, followed by murmuring solos from Kathryn Meany Wilson’s English horn.

Petrenko, a master of balances, kept the muted strings at a hushed level of mysterious sound, dotted with glimmers of celesta. In the second half of the piece, Petrenko emphasized the sudden starts and stops of the trickster spirit, which evaporated with the final twitter of the piccolo.

Edgar Moreau joined the NSO as soloist in Saint-Saëns’ Cello Concerto No. 1, with impressively subtle results. Since winning the Young Soloist Prize at the 2009 Rostropovich Competition at 15 years old, the French cellist has enjoyed a stellar career. The withdrawal of American cellist Sterling Elliott from this program months ago, due to an unforeseen schedule conflict, led to Moreau’s long overdue debut with the NSO.

Moreau’s strength lay in his burnished tone, put to refined use in the more lyrical passages of this beloved concerto, especially rising into a luscious tone on the highest string. After some reflective moments in the opening section, Moreau joined the NSO expertly in an urbane allusion to the rhythm of the minuet in the second section, followed by some quicksilver passages in the cadenza, interwoven with orchestral responses.

Edgar Moreau performed Saint-Saëns’ Cello Concerto No. 1 Thursday night. Photo: Pascal Assailly

The dreamy transition to the closing section, with more ardent playing from Moreau, led to a thrilling conclusion. Moreau moved with clarity through incisive runs and groaning octaves, making a spectacular ascent on a series of flawlessly tuned harmonic notes. Some of the trickier ensemble coordination in this rapidly paced section did not come together perfectly. That may have been due to the loss of rehearsal time earlier in the day, when a bomb threat, directed at the Shen Yun performances in the Opera House closed down the Kennedy Center.

Moreau, acknowledging the hearty ovations of the crowd, offered a serene encore, a reserved, finely nuanced rendition of the Sarabande from Bach’s Solo Cello Suite No. 3. Petrenko’s comment at the start of the concert rang true at such a moment.

Bombast was back on the menu for the second half, featuring Petrenko’s blood and guts interpretation of Tchaikovsky’s epic Manfred Symphony. Based on the dramatic, often supernatural poem by Lord Byron, it tells the story of a nobleman in the Alps, cursed by an unnamed crime committed with his great love, Astarte. Byron, often given to autobiographical inspiration, likely had in mind his own scandalous liaison with his half-sister Augusta.

Petrenko drew forth blazing sounds from all quarters of the orchestra. The low strings opened the first movement with weighty strikes, and the brass, led by the trumpets and trombones, gave incisive power to many loud sections, especially the funeral march-like music. Soft sounds provided dramatic contrasts, especially the bubbling woodwinds and swirling strings of the second movement, depicting an Alpine fairy appearing to Manfred in a waterfall.

Fine solos from oboe, French horn, and offstage bells gave a pastoral sheen to the third movement, a depiction of life in the mountains that goes on at considerable length. The sprawling nature of the piece became overwhelming in the fourth movement, with its depiction of a demonic orgy in the infernal palace of an evil spirit. An awkward fugue evoked the swirling dance of the evil spirits, but a fine solo section for two harps, played with power and precision, marked the ultimate salvation of the doomed Byronic hero.

The program will be repeated 8 p.m. Saturday and 3 p.m. Sunday. kennedy-center.org