Cage-ian chaos shatters Feldman’s serene spell at Linehan Hall

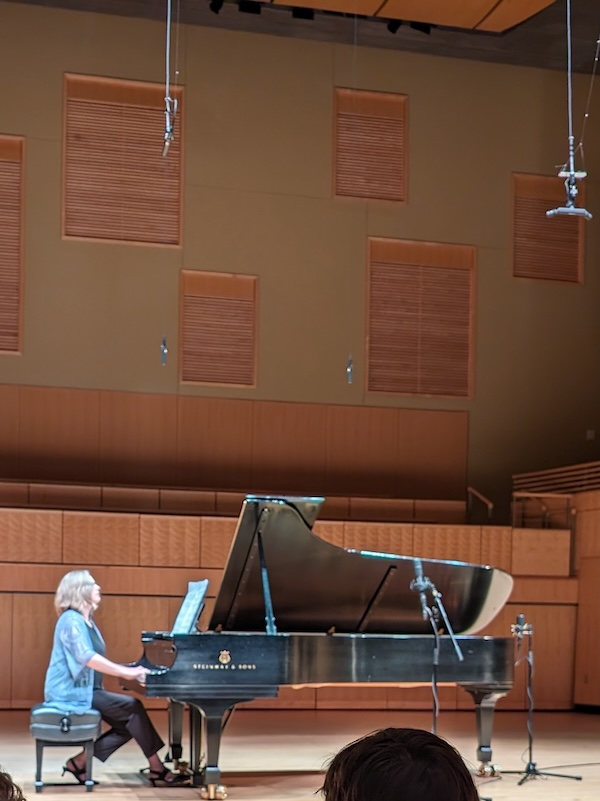

Amy Williams performed Morton Feldman’s Triadic Memories Wednesday night at Linehan Concert Hall at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Photo: WCR

If any composer’s music might benefit from an occasional loud surprise, it is that of Morton Feldman. Toward the end of a performance of his Triadic Memories, heard Wednesday night in Linehan Concert Hall at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, pianist Amy Williams got one.

This slow-moving exploration of repeated dissonant patterns, lasting over an hour while never exceeding the dynamic marking of ppp, was interrupted by a fire alarm. The culprit, according to Thomas Moore, UMBC’s director of arts and culture, was a fog machine being used in the dress rehearsal of a production of Bryony Lavery’s play Slime, which opens today in a theater in the same building.

Feldman composed Triadic Memories in 1981, describing it as the “biggest butterfly in captivity,” referring to the vast length of many works from the American composer’s final decade. Believing that musical form “no longer exists,” he sought to “substitute the word scale or proportion.” With its slowly evolving reiteration of motifs, the piece is something like a passacaglia but without a consistently repeating bass line.

Williams, a pianist who is also a composer, played the piece in a rather straightforward way, opening at a relatively brisk tempo and proceeding without much fuss over complex rhythmic details. Feldman indicated no tempo or metronome marking, and recordings by Aki Takahashi and Roger Woodward, the two dedicatees of the score, vary widely in duration. There is no need to drag out the piece, except to enhance the sense of meditative expansion: discounting the time waiting for the alarm to be turned off, Williams finished in about 70 minutes.

One of the triads “remembered” in the title is perhaps G minor, hinted at in the piece’s opening measure. The right hand, in the extreme treble range, oscillates between G and B-flat, while the left hand’s first note, in the deep bass, is D, in a pattern involving three other notes that is heard over and over, in rectus and inverted forms. With the sustaining pedal partway engaged, called for by the direction “1/2 pedal” in the score, Williams let the piece unfold serenely..

The patterns and repetitions in the music seem regular enough to be predictable but are not. Feldman collected 19th-century Turkish carpets in this part of his life: “Music and the designs or a repeated pattern in a rug have much in common,” he wrote. The arabesque patterns used by Turkish artisans, while appearing symmetrical, often display a studied irregularity, thought to be a visual aid for meditation.

Spread out over such a long period of time, the piece played tricks on the ears. Dissonant clashes seemed less apparent when the notes were separated by many octaves, becoming more concrete as they drew closer. The other element that makes the precise duration of the piece hard to predict is the many cells of one to four measures that can be repeated by the performer. In line with other performances of the work, Williams took these repeats from a couple to several times.

The piece does not reveal itself metrically until about half-way through, when the 3/8 time signature is finally made clear in patterns of three even eighth notes. Williams seized on the even duple rhythms of larger chords that came slightly after that, exceeding the dynamic marking just slightly and then returning to the calm stasis of before. She gave a somewhat uneven twist to another prominent motif, the stream of sixteenth notes noodling around the minor third from C to E-flat, differentiating between the different meters Feldman notated.

It was just after that point, about fifty minutes into the work, that the fire alarm sounded, and the performer and the small audience had to exit the building for a few minutes. Almost providentially, Williams had reached the point in the score where there is a very long, very low dissonant double trill in both hands, leading to a series of repeated single notes or clusters. The obstinate bleats of the fire alarm, which sounded curiously like those repeated notes, broke the spell of the music.

After the alarm had been cleared, Williams reappeared and began again with that same low rumbling trill. She then took about fifteen more minutes to complete the piece, sinking the listener back into the final phases of Feldman’s ideas as best as possible. With a few upward rising arpeggiations and the tentative gesture toward a hypothetical key center of C, Williams brought the piece to an end. In a sense, the random intervention of the alarm had further extended the “disorientation of memory” that the composer said was his aim.

The wind quintet District5 plays music of Hildegard von Bingen, Gesualdo, Salonen, Haas, and others 7:30 p.m. April 7. music.umbc.edu