Opera Lafayette enters new era by reaffirming French baroque focus

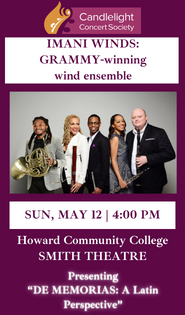

Christopher Rousset (at harpsichord) led Opera Lafayette in a French Baroque program with bass-baritone Jonathan Woody (center) Wednesday night at the Kennedy Center. Photo: Caitlin Oldham

Opera Lafayette announced this summer that its founder, Ryan Brown, would be stepping down at the end of its 30th anniversary season in 2025. The first step of the transition to its new artistic director, Patrick Dupre Quigley, is a season led by guest conductors.

Esteemed French harpsichordist Christophe Rousset kicked things off Wednesday night, in the Kennedy Center Terrace Theater, with a program of rarefied music from the grand siècle. The focus of the evening was François Couperin, represented most beautifully by two instrumental suites. Couperin composed these pieces, known as the Concerts royaux, for the Sunday chamber music entertainments hosted by Louis XIV. In his preface to the first publication of these pieces, Couperin stated that they could be played on the keyboard alone, or with the accompaniment of a few instruments.

Rousset, like Couperin in his original performances, played the harpsichord and shared the score with viola da gamba player Joshua Keller, baroque flutist Immanuel Davis, and violinist Jacob Ashworth. Flute and violin alternated on the treble part, movement to movement, coming together in unison at the end.

Davis distinguished himself with a silvery, delicate sound on the baroque flute, made of wood, playing the odd-numbered movements in Concert No. 7 from Couperin’s second collection of these Concerts Royaux, titled Nouveaux concerts, ou les Goûts réunis. In the other movements, Ashworth’s violin was played with excellent intonation, if more piercing in tone and an occasional scratch on the gut strings. The flute’s graceful “Sarabande grave” and the detached articulation in the “Gavotte” proved highlights, with flute and violin combined in the concluding “Sicilienne.”

On the second half, Concert No. 3 from the first book of Concerts royaux charmed as completely as it had when Rousset led it with his own ensemble, Les Talens Lyriques, for the Couperin anniversary at the Library of Congress in 2018. The sense of an intimate private performance for the royal ear came across in the complex loops of sound spun forth in alternation by flute and violin.

By this point, Keller’s viola da gamba, plagued by intonation issues in the first suite, relaxed into its role, half-continuo and half-solo instrument. The lengthy “Musette,” an evocation of the rustic folk bagpipe, unspooled over the steady drone of Rousset’s left hand at the harpsichord, with the violin taking over the treble part from the flute in the minor section. The simplicity of this music, which Couperin marked “Naïvement,” was a delight, followed by a complex closing “Chaconne,” with flute providing echo effects to its doubled statements with the violin.

Rousset anchored this appreciation of Couperin Le Grand on the cantata Ariane consolée par Bacchus, which he rediscovered a few years ago in a manuscript collection of mostly anonymous French cantatas. Bass-baritone Jonathan Woody took the solo part with an animated freedom in the recitatives, impressively singing all three cantatas on the program from memory, with especially agile runs and compass-spanning arpeggios in the fast arias.

In contrast to his performances in other repertoire, Woody adopted a more affected style in these pieces. His French diction was sometimes impenetrable, especially in fast-moving passages, and an often nasal placement rendered the tone more shallow. The choice of violin over flute in the vocal selections constituted a loss in some ways, as did the lack of the theorbo, heard on Rousset’s recording, to add variety to the continuo line.

Cantatas by two Couperin contemporaries bookended this diverting program, beginning with Louis-Nicolas Clérambault’s La Mort d’Hercule, a tribute to the death of Louis XIV, who was often pictured in art as Hercules. Both Ashworth and Woody thrilled in the extravagant melismas of this cantata’s fast aria, “Courez, ravagez la terre,” guided by the consummate musicality of Rousset’s judiciously rendered continuo playing.

The final selection, L’Enlèvement d’Orithie by Michel Pignolet de Montéclair, was the most demanding and flashy of the three cantatas. Woody’s voice appeared to strongest effect in fast-moving pieces, like the aria “Sortez, tonnez, vents furieux,” as the god of the north wind, Boreas, summoned a storm to help turn the heart of the nymph he pursued unsuccessfully. Violin, viol, and harpsichord provided rumbling accents of thunder and lightning in the subsequent accompanied recitative.

Ashworth rose to the occasion in the closing sections of this remarkable cantata, with plangent tone in the solo “Air de Violon,” a sort of instrumental evocation of the success of Boreas’s efforts, in the form of a tender Rondeau. The final aria, “Amants, tout cède à la constance,” featured more brilliant violin passagework.

Woody had his strongest outing in the exceptionally fine encore, the plaintive aria “Vos mépris” by Michel Lambert, from the generation of composers before Couperin, last heard a decade ago from none other than Opera Lafayette.

The program will be repeated 7 p.m. Thursday at the Kosciuszko Foundation in New York City. operalafayette.org