Wu Han and friends conclude Wolf Trap season with jazz-inspired program

Pianist Zhu Wang performed in the Wolf Trap chamber concert Sunday afternoon. Photo: Jiyang Chen

In the 1920s American jazz began to cross-fertilize with other styles of music, inspiring many classical composers in Europe and the United States. The final program of Wu Han’s fourth season as artistic advisor at Wolf Trap—she will be back in the fall—was heard Sunday afternoon in the Barns, examining this interaction from both sides of the exchange.

Maurice Ravel took up the blues in the middle movement of his Violin Sonata No. 2, composed from 1923 to 1927. Daniel Phillips, one of the two brother-violinists in the Orion String Quartet, and Wu Han gave the first movement, a rather austere Allegretto, a laid-back interpretation, recombining the various motifs coolly, including one the composer likened to a hen clucking.

The “Blues”second movement ambled along in no hurry. Some performers jazz up the written score a bit, as Phillips did by adding bends here and there. His dry pizzicato passages recalled the banjo, the signature American instrument of jazz in the period Ravel heard it. Phillips dialed up the energy for the last movement, a crisply ordered perpetuum mobile, with Wu Han’s precise accompaniment helping to underscore metric shifts.

Although most of the program dealt with classical composers inspired by jazz, the Orion String Quartet next presented the final four movements of Wynton Marsalis’s String Quartet No. 1 (“At the Octoroon Balls”). Marsalis composed the work in 1995 for these musicians, premiered at a concert co-presented by Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center and Jazz at Lincoln Center, which Marsalis has led since 1987.

The process was the reverse of what Ravel did, as Marsalis used the “foreign” string quartet to produce music he knew in his native New Orleans. In “Many Gone,” cellist Timothy Eddy railed on his solo parts, said by Marsalis to represent a minister’s fiery preaching. Daniel Phillips, on first violin, led the section identified by the composer as a “field holler,” with the quartet even stamping their feet rhythmically on the floor toward the end.

Inspired by Duke Ellington’s musical depiction of trains, “Hellbound Highball” was a locomotive scherzo, with the lower three instruments imitating the clack of the tracks and the first violin honking in loud clusters. Some glissando howls and other odd effects revealed the influence of Bartók’s string quartets, which Marsalis had studied at the time.

In “Blue Lights on the Bayou,” which Marsalis likened to a New Orleans funeral procession, the three higher instruments planed together on glassy clusters over a tense cello pizzicato. Marsalis infused the style of Scott Joplin into the last movement (“Rampart Street Row House Rag”), with a few allusions to common Joplin ragtime gestures. Overall the piece sounded looser than in the quartet’s 1999 Sony recording.

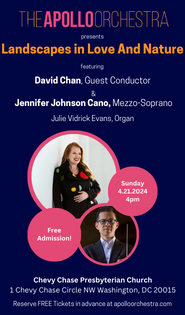

The highlight of the concert was the piano quintet version of Darius Milhaud’s music for the 1923 ballet La création du monde. Set to a story by Blaise Cendrars about the world’s beginning according to African folk mythology, Milhaud’s score drew on jazz elements he had heard on visits to London and the United States. Young pianist Zhu Wang anchored the piece with subtlety of dynamic control and ensemble sensitivity.

Wang took the first movement’s melancholy tune, given to the alto saxophone in the original score for eighteen musicians, answered by violinist Todd Phillips, now on first violin. The group grooved on the second movement’s theme, a jazzy subject treated fugally. At full tilt, the strings let loose a magnificent explosion of sound. In the third movement (“Romance”), Wang’s smoky touch at the keyboard gave the piece an alluring rhythmic lassitude.

Wang again held together the zippy tempo for the fourth movement (“Scherzo”), crushing the demanding piano part. The strings revisited the score’s various themes in the slow introduction to the final movement, with Wang’s unflappable presence driving the faster, syncopated section. Although the alto saxophone took the place of the viola in the original score, violist Steven Tenenbom took up that part at the end, leading to a warm conclusion glistening with dissonance.

Wu Han seconded Wang on the primo part in the final work, a delightful arrangement of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue for piano, four hands, by Henry Levine. Wang started the piece off with a piano approximation of the braying clarinet solo. In fact, he had to start it twice, after a problem with the score not appearing on one of two electronic devices the musicians used. Sadly, this was only the first of such technical mishaps, which inevitably dampened the overall effect of the piece.

The dueling tablet page-turning complicated the interplay of the two musicians’ arms, part of the balletic fun in four-hands performance. In spite of the technical issues, all covered almost imperceptibly by the performers, the rapport between the two pianists made for an engaging whole. Running figures up or down passed seamlessly from one to the other, and joint syncopated attacks hit with impressive unity. Wu Han, as Martha Argerich did at her Lugano Festival, continues to feature young pianists of great promise in this stimulating repertoire.

Subscriptions are on sale for the 2022-2023 season of Chamber Music at the Barns, which will include concerts by violinist Paul Huang, the Emerson String Quartet, and the Escher String Quartet with pianist Gilbert Kalish, among others. wolftrap.org