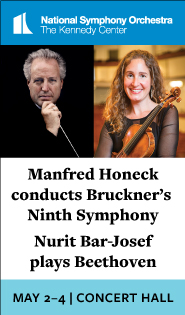

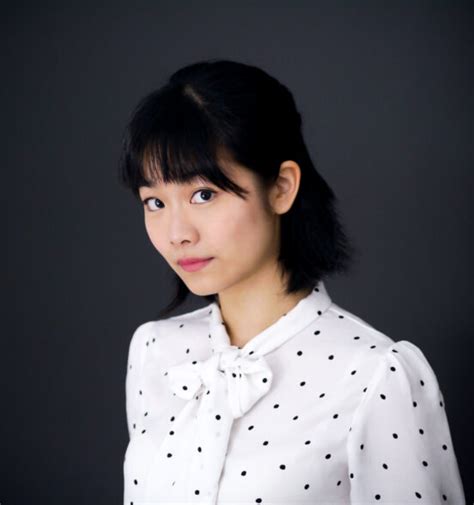

Washington Performing Arts and pianist Tiffany Poon return to the stage with smart, insightful Schumann program

Pianist Tiffany Poon performed Sunday at the Kennedy Center Terrace Theater, presented by Washington Performing Arts. Photo: Sid Baker

Everyone was feeling misty-eyed Sunday afternoon as pianist Tiffany Poon took the stage of the Kennedy Center Terrace Theater.

Jenny Bilfield, president of Washington Performing Arts, admitted to feeling “a little bit choked up,” as Poon’s debut came 646 days since the presenter’s last live concert in this venue. At the end of the program, Poon wiped away tears, too, confiding to the audience that she had not played in front of live listeners since September 2020.

The 24-year-old pianist, born in Hong Kong but now residing in New York, has over 300,000 subscribers to her YouTube channel. Yet in spite of her online appeal, this program of music by Robert and Clara Schumann was anything but watered-down populism.

Poon’s selections offered a tour through the love dialogue left by the Schumanns in music notation, both before and after their marriage in 1840. In September, Poon even recorded videos of herself playing works from this program on the couple’s historical pianos at the Schumann Haus Zwickau.

The concert opened with Robert’s Kinderszenen, composed in 1838, reportedly in response to a comment from Clara, nine years Robert’s junior, that he often seemed to her “like a child.” Poon took a long pause before beginning the first piece, allowing the hall to settle and quiet. She drew forth a startling range of subtle touch at the keyboard, generally keeping rubato to a minimum.

This choice of guileless simplicity echoed Schumann’s remark to Clara that in order to like these pieces, “you must forget that you are a virtuoso.” The first movement was wistful without becoming overly sentimental, with faster movements jaunty but not explosive. At the same time, the famous seventh piece, “Träumerei,” fell a bit flat. When Poon added more effusive rubato, as in the tenth movement, it stood out by comparison as an expressive device carefully added rather than omnipresent.

Having asked the audience to applaud only when she stood after each set, Poon elided the end of Kinderszenen with the start of the next piece, Robert’s Arabeske. It fit in tidily due to the pianist’s similar approach, cautious in tempo and strong on gradations of soft phrasing, almost as if it were a forgotten final movement of the preceding work.

The first half ended with Clara’s Piano Sonata in G Minor, a work she never performed in public and left unpublished. She composed it in the two years following the marriage, as a sort of love letter, giving Robert the first two movements as a Christmas present, followed later with the Adagio and Rondo movements. This was a Schumann tradition, as husband and wife exchanged private compositions with one another at Christmas and other holidays.

Published belatedly in 1991, the sonata was revealed as a work of modest achievement. Poon’s romantic phrasing suited the fervent melodic writing in the first movement, but the avoidance of rhythmic give and take made the slow movement rather four-square. More life came into the work in the playful Scherzo, detached and almost Haydnesque in its wit, while the snappy Rondo finale remained focused on simmering inner lines.

The second half revealed Clara’s compositional skill in a stronger light, with virtuoso character pieces from her collection Soirées Musicales. The style of the Notturno and two mazurkas was indebted to Chopin, whom she had met and impressed with her playing in her father’s house in 1835. Poon stretched the tempo of the Notturno to expressive effect, giving a creamy softness to the bel canto flourishes of the right hand, again recalling Chopin.

The Mazurka in G Minor had a more heroic cast, contrasting nicely with a folk-styled middle section over a rustic drone in the left hand. The Mazurka in G Major had a more dynamic sweep, with a daring trill section before the return of the main theme. As this piece of Clara’s is quoted at the start of the concert’s final work, Robert’s Davidsbündlertänze, Poon again elided the two works with almost no pause.

Robert also attributed the inspiration for the Davidsbündlertänze to Clara, saying that she was “practically my sole motivation” for writing it. Rather than dances, the pieces are character pieces attributed to Florestan and Eusebius, as if the two sides of Schumann’s musical personality were having a heated conversation about music. The Davidsbündler, or League of David, was the idealistic music society of the new composers fighting against the Philistine of conservative taste.

Poon finally unleashed some rawer sound for the brash, heroic Florestan pieces in this set, although without the full abandon that might have made them more exciting. A sense of self-control generally remained. More soft dreaminess characterized the Eusebius movements, as in the velvety rolled chords in the seventh movement, with its delicate stops and starts. Poon’s range of soft touch amazed, with the music-box tune of the fourteenth movement or the distant sounds of the seventeenth movement heard as if through an obscuring veil.

The “token of love” from husband to wife would be reciprocated in Poon’s cannily chosen encore, “Albumblätter I,” the fourth movement of Robert’s Bunte Blätter, the collection where some of the pieces cut from Kinderszenen would be included. Clara would later pen a set of variations on this melancholy tune, given mournful poignancy by Poon.

Washington Performing Arts presents mezzo-soprano J’Nai Bridges with the Sphinx Symphony Orchestra and Exigence Vocal Ensemble, 8 p.m. February 1, 2022. washingtonperformingarts.org; 202-785-9727