NSO oboist Stovall superb in a belated Mozart debut

Nicholas Stovall performed Mozart’s Oboe Concerto with the National Symphony Orchestra Tuesday night at the Kennedy Center.

A year after transitioning to the position of conductor laureate, Christoph Eschenbach is offering a love letter to the musicians of the National Symphony Orchestra. Principal violist Daniel Foster took center stage last week, and on Tuesday evening Eschenbach featured principal oboist Nicholas Stovall in a concerto the NSO performed, somewhat surprisingly, for the first time in its history.

Even though only three principal musicians are performing concertos with the NSO during this pre-summer extended season, Rossini’s Overture from Guillaume Tell offered mini-spotlights to several other musicians. Principal cellist David Hardy, assistant principal cellist Glenn Garlick, and three of their colleagues played radiantly in the opening dawn section for five solo cellos, Hardy gliding sweetly up the A string to a pure harmonic note.

The trombones rattled loudly in the wild outburst of the storm and English horn player Kathryn Meany Wilson traded warm, relaxed phrases with flutist Aaron Goldman in the pastoral section. Finally the trumpet gave focused brilliance to the famous conclusion, followed by Eschenbach graciously acknowledging the soloists.

Mozart composed his Oboe Concerto in C Major in 1777, for the oboist Giuseppe Ferlendis from Bergamo. It may be more familiar in the composer’s adaptation as the Flute Concerto in D Major, but, amazingly, this was the first time that the NSO played the original version for oboe. Mozart’s concerto could have no better exponent than Stovall, whose performance of Mozart’s Oboe Quartet was one of the highlights of the NSO in Your Neighborhood outreach program this past January.

In the first movement, Stovall played the many running passages cleanly but also expressively, carefully negotiating the shifts of register and holding the long, limpid high C notes effortlessly. The second movement played to Stovall’s strengths, a plaintive legato tone buttressed by unflagging breath support. Eschenbach led a small orchestral ensemble with care, balancing his soloist sensitively with just enough sound.

The finale was perky and active, with Stovall adding a few little ornaments to the melodic line with careful dynamic contrasts of loud and soft. Stovall played his own cadenzas in each of the movements, and they were diverting and well-rounded, especially in the outer movements. He pulled out a range of techniques, setting many of the themes in minor keys, interpolating some perfectly realized high notes, and mixing the themes into interesting patterns of arpeggiation and bariolage.

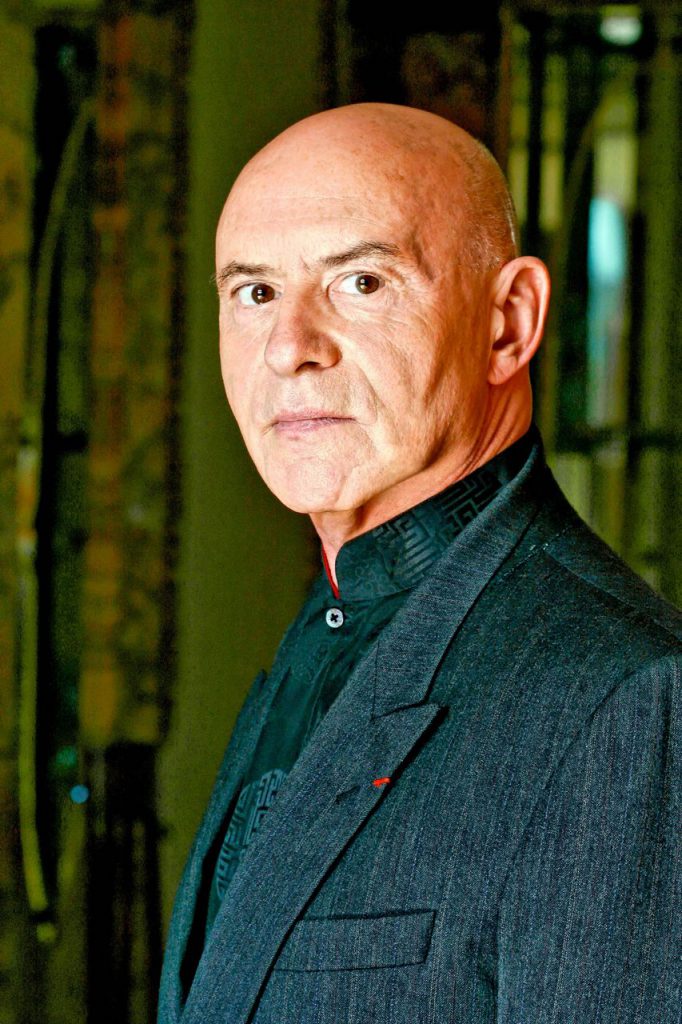

Christoph Eschenbach

Mendelssohn’s Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream put the woodwinds back in the limelight, with beautifully tuned high chords on the mysterious opening and closing harmonies. In this piece, Eschenbach seemed to fall back into old habits, as he launched with some agitation into the fast section, seeming to be at odds with the strings on the pacing. As a result the piece did not quite shimmer as it should, although as that music returned Eschenbach settled for a slightly calmer tempo.

Eschenbach was not able to complete his cycle of the Beethoven symphonies during his tenure as music director. He tied off one of those loose ends with a spirited performance of the composer’s Fourth Symphony. It is an ebullient work, far from the “slender Greek maiden between two Norse giants,” as Robert Schumann put it, and Eschenbach played up its explosive qualities, in the syncopated themes and big dissonant structures.

Both the mysterious slow introduction to the first movement and the Adagio of the second movement felt rushed in this performance. In the latter the little dotted-rhythm theme that appears from time to time, like a heartbeat, revealed Eschenbach’s tempo seeming to slow down over the course of the movement. On the other hand the slippery scherzo and wide-eyed trio in the third movement buzzed with energy, as did the even faster finale, dazzling with a frenetic edge.

The program will be repeated 8 p.m. Wednesday. kennedy-center.org; 202-467-4600.

Posted Jun 15, 2018 at 1:11 am by Adam

You left out the best part: Stovall’s cadenza in the third movement ended with an arpeggio riff designed to recall the English horn solo in the Rossini. It was a musical joke Mozart would have appreciated (and plenty of the audience did).