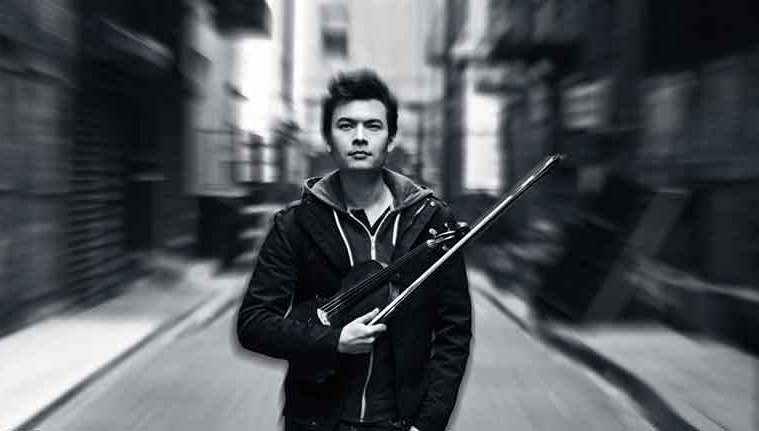

Violinist Stefan Jackiw strives to bring out the grit and nostalgia of Charles Ives

Stefan Jackiw will perform the complete violin sonatas of Charles Ives with Jeremy Denk Friday night at The Clarice.

Charles Ives is still a problem.

Our current era accepts and name-checks Ives as one of the greats, essential to the American classical music tradition and one of the most important figures in the rise of modernism in the early 20th century. But like an aging movie star from decades past, or a once-prolific writer about whom one might wonder if they were still alive, Ives is spoken and written about far more than he is heard.

He is now in the canon of the greats, but his work does not sit inside the skin of musicians and listeners the way the music of the other greats—Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, etc—does. Listening to his music is still a challenge, not to the sensibilities but to the intellect. How does one approach the music? How does one get into it?

This is the challenge that violinist Stefan Jackiw is tackling in his upcoming, slow-rolling concert tour of the four Ives Violin Sonatas with pianist Jeremy Denk. Their itinerary brings them to The Clarice Friday night.

This is the second time around the country with this music for the duo. Their previous 2015 tour featured an idea they are reviving this year: collaborate with a vocal group local to each venue and have them sing some of the original music material—songs and hymns—that Ives used in his quilt-like approach to turning memory into music.

Speaking on the phone, Jackiw described that as a mutual decision the pair come to before the first tour. The idea was less musicological than social: give the audience some idea of Ives’ musical past and personality, a sample of some of the things he loved. And the things Ives loved, less his philosophical and aesthetic concepts than the actual stuff of life itself, is the best first step toward his music.

“People get lost in the idea of him,” Jackiw says, and they “lose track of the music.” Because what is in the music, underneath the stream-of-consciousness forms, the moments of seemingly awkward rhythms and banging dissonances, the willful iconoclasm, is memories.

“He’s the most romantic composer,” Jackiw goes on, “with Proustian obsessions that you see in Brahms.” That is the bedrock of all of Ives’ music. As a young composer, who was indebted to the example of Brahms, and the memories were part of the surface and structure of works like his Symphony No. 1. Once he left that specifically European past behind and unveiled his own true voice as a composer, the memories sunk deeper.

Ives famously uses music that came out of his memories; Protestant hymns, popular songs of his era, patriotic music. These are sprinkled throughout his mature work, and in the violin sonatas one hears snatches of “Shall We Gather at the River,” “Turkey in the Straw,” “Battlecry of Freedom,” “Watchman,” and “There’s a Clearing.” This is so well-known about him as to seem no longer remarkable, but it is neither quirk nor technique–it is the point and meaning of Ives’ work.

This is nowhere more true than in these sonatas. The four came, for the composer, relatively quickly, during the same extended period that produced the essential “Concord” Sonata and the Symphony No. 4, great public expressions of Ives’ aesthetic, social, and moral values.

Yet the Violin Sonatas go even further. They are not extroverted, they are not a statement, they are an overheard conversation Ives is having with his past and his idealization of it: his lost paradise of small-town Danbury, Connecticut, his father, an eccentric bandleader whose failed musical experiments paved the way for his son’s successful ones, and his dreams of what he thought his country was.

The constant dialogue between violin and piano, with ideas and memories bounding off one another, sometimes gradually, other times at a giddy pace, opens up shining windows into his memories. They come, pleasant ones and distressing ones, unbidden, just as they do for us in the streets, in our homes.

“He captures in sound what we all experience in life,” Jackiw says. “His music is a time machine, bringing these lost tableaux to life.”

But unlike his deeply sympathetic contemporary and peer, Gustav Mahler, Ives had no self-consciousness about turning those memories into art. He was a composer, so he transforms the tunes he uses, but to Ives using such material was a natural part of his musical language, which he felt was a plainspoken expression of basic humanity and the mysteries of the soul. That those things could not be fully comprehended in words, and that the music could no be fully explained, was the point. The music spoke plainly, and it was a measure of its greatness that of what it spoke could never be finally determined.

And that is the real challenge in Ives, not just in hearing him but in playing him. When he first approached the music, Jackiw himself turned to Ives’ great inspiration, Brahms, who prepared him for this “curmudgeonly, crusty old New Englander.

“That kind of unburnished sound,” that requires an amateur’s attitude and spirit, “is not something we work on! Trying to find that grittiness was the biggest challenge for me.”

Jackiw hears an “unschooled wildness” in the music, which is not a lack of compositional craft but a lack of self-consciousness about how one is supposed to sound, about what art is supposed to be. The goal is “unrefined ecstasy,” because “we the people are creating this experience.”

For decades, the conventional wisdom about Ives was that he was a primitive artist and that as glorious as his concepts could be, they were unsupported by his compositional craft, which was rudimentary. There was never any truth to this, and Kyle Gann completely demolished the argument in his 2017 monograph, Charles Ives’s Concord: Essays After a Sonata.

But failure is part of all creative endeavors, and Ives did fail in instructive and constructive ways.

“The more I get to know the music, I feel he was shackled by the limitations of notation,” says Jackiw. Which in Ives’ case was not the inability to write music, but developing a new language out of the old, in the fundamental modernist manner. The old worlds and syntax and grammar could not express his thinking, and so he had to create new ones.

This dual striving, reaching deep into himself for expression and far outside himself for means, comes together in the sonatas. They are equally poignant, experimental, confident, and uncertain where they should go next. This range is especially broad between Sonata No. 2, which is contemplative and gentle throughout, and No. 4, which stops in the middle of a phrase.

None of these qualities are at odds, through they are still unfamiliar in classical music. The art of composing is commonly, and accurately, thought of as Apollonian, a purification of ideas into abstract structures. Ives was an exception—to him it was an extension of the complexity of lived life.

Playing Ives, and listening to Ives, Jackiw pointed out, means that “you have to digest [his music] and make it your own”—then forget it all and just play. “That’s how you bring Ives’ world to life.”

Stefan Jackiw and Jeremy Denk perform the four violin sonatas of Charles Ives 8 p.m. Friday night at The Clarice at the University of Maryland. the clarice.umd.edu.