Biss, Brentano Quartet explore composers’ late works at Shriver Hall

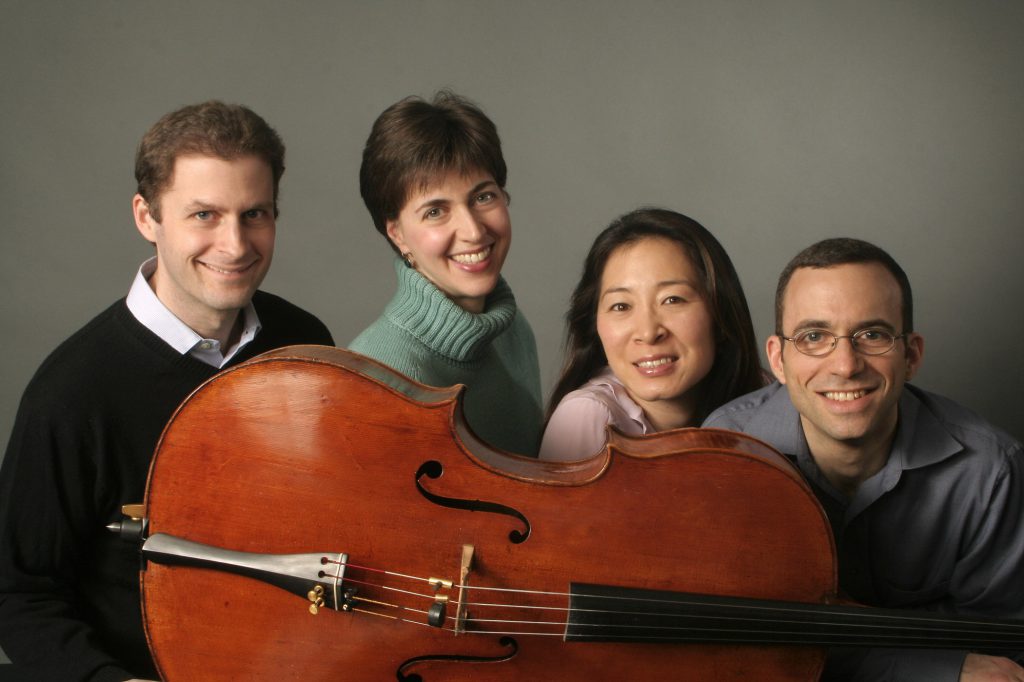

The Brentano Quartet performed Sunday night in the Shriver Hall Concert Series.

Jonathan Biss and the Brentano String Quartet shared a program Sunday evening at the Shriver Hall Concert Series at Johns Hopkins University. Biss and the quartet have been performing throughout the U.S. and Europe this season. Yet rather than performing together, their programs consist of Brentano and Biss alternating pieces, creating an interesting middle ground between a chamber concert and a solo recital.

The Biss/Brentano collaboration arose from a project devised by Biss to explore the late works of composers and the “new directions” that different composers have taken over the centuries. Sunday’s program consisted of four selections from J.S. Bach’s Die Kunst der Fuge, a sampling of pieces from the seventh volume of Játékok, or “games,” by György Kurtág, Benjamin Britten’s String Quartet Number 3 Opus 94, and Beethoven’s final piano sonata, Opus 111.

The Art of the Fugue is Bach’s last major work, and at the time of his death, its contents, though largely finished, were left without any indication as to instrumentation or order. Though most likely conceived on a keyboard instrument, the fourteen fugues contained within it are often performed convincingly by other instruments, especially by string quartets as was the case Sunday evening.

The Brentano Quartet played the first, seventh, fourth, and eleventh Contrapuncti from the set. Each fugue in this work is based on the same theme, and one of the great challenges of performing multiple numbers from the work lies in finding a way to create different characters from pieces derived from the same basic idea. The Brentano members handled this challenge deftly by drawing from a wide variety of timbres and rhythmic characters in each piece.

Throughout all four fugues, they achieved consistent balance that allowed each voice to have clarity without the texture ever becoming crowded.

Jonathan Biss. Photo; Benjamin Ealovega

Next on the program was Jonathan Biss’s offering of six movements from Book Seven of Játékok by the 91-year-old Hungarian composer György Kurtág. Kurtág has been writing books of these small pieces since the early 1970s. Originally intended as educational pieces for children to expose them to contemporary piano music, the project evolved into a wide-ranging expression of Kurtág’s compositional language through miniature forms. The work has grown to eight volumes, and Kurtág continues to add to the set.

These pieces showed Biss at his very best. Much of the music explores the subtle varieties of expressive possibility within a very soft dynamic range, and Biss demonstrated an exacting control of even the faintest pianissimos. He also created striking shifts of color between firm, articulate attacks and more rounded, finessed sounds. In one of the pieces, “All’ongherese,” the music calls for the pianist to play large tone clusters by pressing both palms into the keyboard. Biss delivered all of these with breathtaking dynamic refinement.

Despite the excellent delivery, this quiet, precise music can be challenging to engage with for some listeners, and the rustlings of an unsettled audience provided a disatraction throughout the set.

The first half of the program ended with Brentano’s return to the stage to perform Benjamin Britten’s Third String Quartet. Completed in the final months of the composer’s life, it pays homage to the works of his admired contemporaries, particularly Dmitri Shostakovich, and is often hailed as one of Britten’s finest instrumental masterpieces. The final movement is subtitled La Serenissima in homage to Venice, a city Britten loved throughout his life. The movement contains a musical quote from Britten’s final opera, Death in Venice, completed a few years earlier

From the opening of the first movement, the ensemble moved and breathed as a whole, and played with dynamic intensity and rhythmic vigor. Throughout the work, the performers achieved a very effective contrast between moods of serenity and anxiety that reflected Britten’s psychological state at the time of this composition. The playing in the last movement evoked poignant nostalgia. At the quiet conclusion, the audience held a mesmerized moment of silence before responding with an enthusiastic ovation.

Ludwig van Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 32, Op. 111, made up the entire second half of the program. The first movement of this piece commences with a dramatic leap in the left hand, followed by a chordal outburst of emotional intensity akin to the beginning of the Ninth Symphony or the Grosse Fuge.

Biss convincingly conveyed the manic emotional volatility of this movement, which often leaps from passionate outbursts to intimate reflections. However, he lacked clarity in much of the fiery passagework that runs through this movement, particularly in the fugal development section. At times he seemed to be struggling with the instrument to create an adequately large sound. The second movement is an Arietta theme with eight variations, and has a much more serene, introspective character than the first. Biss seemed more comfortable and returned to form, delivering an exquisite rendition.