UrbanArias tells a real-life American horror story with Hagen’s stirring “Shining Brow”

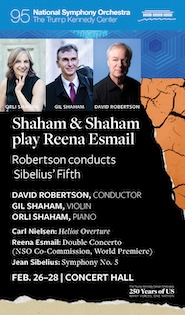

Miriam Khalil and Sidney Outlaw in Daron Hagen’s “Shining Brow” at UrbanArias. Photo: Teresa Wood

The most promising contemporary operas deserve repeated hearings. Too often they do not get them, or composers have to adapt full works for large orchestra as chamber versions for smaller forces. Such is the case with Daron Hagen’s first opera, Shining Brow, since its premiere in 1993 by Opera Madison. UrbanArias has revived this beautiful work in a new version, still for chamber forces, heard on Saturday night at the Atlas Performing Arts Center.

Librettist Paul Muldoon took the story from the most tragic episode in the life of architect Frank Lloyd Wright. After designing a house for the wealthy Edwin Cheney, Wright ran off with Cheney’s wife, Martha “Mamah” Borthwick Cheney. They traveled together through Europe, and then back in Wisconsin Wright built a celebrated residence named Taliesin for her. In 1914, while Wright was away, the estate’s deranged cook attacked Borthwick and her young children, killing them with a hatchet and lighting their bodies on fire with gasoline.

Hagen has acknowledged the influence of composers like Benjamin Britten, Leonard Bernstein, and Marc Blitzstein, and the best of all three of them mingle in the music of Shining Brow. Expressive intervals move in unexpected directions in his melodic writing, making many of the arias’ jewel-like constructions. A facility with jazz extends his harmonic palette, and unusual techniques, like the shouted group monologue of the Taliesin murderer, add a touch of individuality.

Highest praise goes to soprano Miriam Khalil, whose sinewy vocal strength and dark-hued tone brought out the sultry side of the potentially unsympathetic character of Mamah, the unfaithful wife. In the letter scene (“Frank, how much longer must I endure”) at the end of the second act, Khalil’s suavely soft tone and stage presence communicated some of the enthralling power of the woman over the architect.

Ben Wager raged as Mamah’s wronged husband, Edwin, his powerful bass voice matched by a deep vocabulary of grimaces and clenched fists. He was at his best in the angry aria in Act I (“The truth is that my mouth is full of nails”), where the diction was so clear that the lack of supertitles was not a problem, as it was at other points. Mezzo-soprano Rebecca Ringle was dignified as Catherine Wright, the architect’s long-suffering wife, with an abrasive edge in Hagen’s high-flying writing for the role.

Baritone Sidney Outlaw struggled at the top of the central role of Wright, but only at the loud climaxes, where the writing pushes vocal boundaries. He was compelling in the dramatic final monologue of the opera, after Wright learns of the horror that has unfolded at Taliesin, bathed in a lonely spotlight and with admirable subtlety of tone and diction. An African-American playing Frank Lloyd Wright is no more remarkable today than a Caucasian would be in the role of Porgy, and it’s a hopeful sign that racial barriers in opera casting are coming down for good.

Tenor Robert Baker was a careening force as Louis Sullivan, Wright’s mentor. Acknowledging recent scholarship about Sullivan and Wright’s relationship, there was an intense kiss between the two men at the end of Sullivan’s final arietta (“I cry out from the Slough of Despond”). This new “Usonian” version of the opera (the word is borrowed from a coinage of Wright’s), created by Robert Wood of UrbanArias, set and costume designer Grant Preisser, and the composer, still omits the chorus, which sang the most beautiful music in the original opera. It does bring back an extra twenty minutes of music removed in Hagen’s first chamber version.

Preisser’s simple backdrop set piece recalls the Prairie Style private houses built by Wright in this period, with their horizontally sloped roofs and cantilevered extensions. Rolling panels, also in Wright’s abstract geometric style for glass windows, create variety in the staging, directed fluidly by Paul Peers. Intense lighting by Lucrecia Briceno adds to the drama of the Fire Interlude, the stylized depiction of the murders at Taliesin, created instrumentally with the talented chromatic screeching from members of the Inscape Chamber Orchestra.

The Inscape ensemble played at the back of the stage, behind a scrim, with the string trio providing a warm backdrop for the more delicate pieces. Pianist Molly Orlando took on most of the other effects from Hagen’s original orchestration, like the chiming bell that runs through much of the score.

Wood’s conducting kept the performance together, his image projected on screens hanging from the lighting rigs. Singers craning their necks upward to check his beat was one of the rare shortcomings of this otherwise fine staging — that, and an unpleasant fog effect pumped in for the entirety of the performance, which caused some coughing in the house.

Shining Brow runs through October 21 at the Atlas Performing Arts Center. urbanarias.org; 202-399-7993.