WNO’s musically lightweight “Champion,” more theater than opera

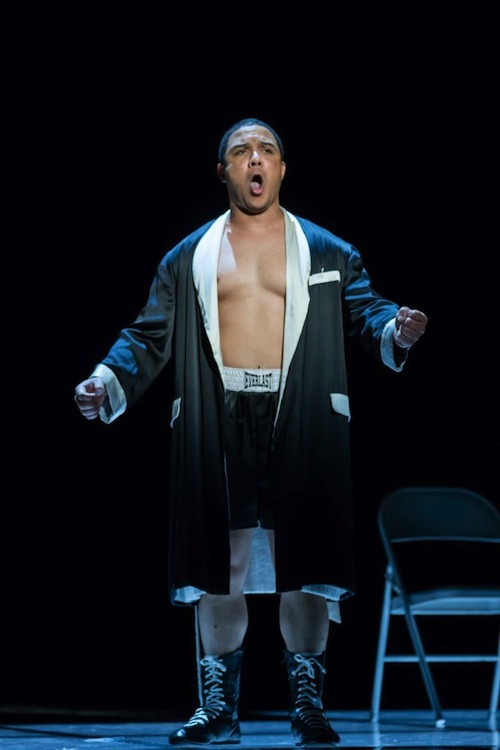

Aubrey Allicock as Emile Griffith in Terence Blanchard’s “Champion” at Washington National Opera. Photo: Scott Suchman

In most of her seasons as artistic director of the Washington National Opera, Francesca Zambello has included a musical. In that slot this year is Champion, Terence Blanchard’s “opera in jazz,” premiered in 2013 by Opera Theatre of St. Louis and revised last year at Opera Parallèle in San Francisco.

Heard at opening night Saturday in the Kennedy Center Opera House, the work seemed more theater than opera, with most of the important dramatic events transpiring in spoken dialogue and even total silence.

The libretto by playwright and screenwriter Michael Cristofer tells the story of Emile Griffith, a boxer remembered principally for his brutal defeat of Benny “The Kid” Paret in 1962. Griffith was incensed by an incident prior to the match, when Paret taunted him with a Spanish slur meaning “homosexual.”

When Griffith saw his chance in the twelfth round, he pinned Paret in a corner of the ring, pummeling him savagely in the body and head, even propping him up so that he could continue to hit him. When the referee finally pulled Griffith away, Paret slumped to the ground and never regained consciousness, dying several days later. The match, although softened in this retelling, was so notorious that television networks were subsequently reticent to show boxing matches on the public airwaves.

Blanchard revised the orchestration of the work last year, and he should have taken the opportunity to trim some of the opera, which is repetitive and runs long. Part of this is the fault of the libretto, like David Blalock’s poor Ring Announcer, who has to make do with the same joke several times until it is thoroughly stale. Some of the blame falls to the composer, who like the librettist undertook his first opera in this work. Blanchard’s primary work is as a film score composer, most importantly and to brilliant effect in the movies of Spike Lee, and much of the evening fell into an episodic rhythm which only contributed to the feeling of longueur.

Most of the leads reprised their roles from the premiere in St. Louis. Bass Arthur Woodley was affecting as the older Griffith, shown in the final stages of the boxer’s dementia that ended his life. Because of the clumsy amplification of the singers, it was difficult to get a true sense of any of the voices, but Woodley struggled at the top of the role’s range. As the young Griffith, bass-baritone Aubrey Allicock was not as effective in the emotional range of the character but had the necessary swagger for the role.

Washington, D.C. native Denyce Graves went after the best and worst in her startling portrayal of the boxer’s mother, Emelda Griffith. The mezzo-soprano, a beloved singer locally, was rough of voice, but she threw all her resources at the character, a boozing opportunist who abandoned Emile and her other children but returns to take advantage of his success. It was a dramatic success, if not quite pretty to hear.

Domingo-Cafritz Young Artist Leah Hawkins nearly stole the show with powerful appearances as the sadistic Cousin Blanche and Griffith’s neglected wife, Sadie. Young Samuel Grace was worthy of his last name in a poised performance as the boy Emile, his treble voice, amplified but still exposed, sounding quite lovely.

Suffering from a cold, Wayne Tigges had a rough start as Griffith’s manager, Howie Albert, and soon had to settle for acting the role, while the cover singer, Samuel Schultz, provided the sound from a music stand to one side of the stage. Contralto Meredith Arwady also reprised her braying, foul-mouthed performance as Kathy Hagan, the proprietor of the gay bar that Emile begins to frequent. Although this was supposedly a side of the boxer’s life he tried to keep hidden, the bar’s outrageous drag queens returned in almost every scene, including Emile’s wedding.

George Manahan, who conducted the work’s premiere, made a capable company debut at the podium. Coordinating the singers, the orchestra, and the jazz quartet added to many of the scenes still proved difficult at times. Director James Robinson adapted the premiere production from St. Louis, with some spatial separation of the characters helping to communicate the time shifts. The main focus of the rudimentary set design (by Allen Moyer) was the same metal catwalk stretching across the stage from Zambello’s staging of Dead Man Walking, which is running in alternation with this work. Huge screens did most of the work setting the tone, showing video projections (designed by Greg Emetaz).

Champion runs through March 18. kennedy-center.org; 202-467-4600.

Posted Mar 06, 2017 at 10:32 am by Fulgencio

I, Fulgencio, was quite moved by Emile’s tale. And although the show made for a nice evening out with my Armando, I did not particularly enjoy the production unfortunately and agree with your criticism. To be fair, I am more of a Puccini kind of guy.