A pianist’s sensational debut and a somber symphonic tribute from Conlon, NSO

James Conlon has a long history with the National Symphony Orchestra, going back to his apprentice years under Mstislav Rostropovich. He came to mind as a possible successor to Christoph Eschenbach, especially after he led a gorgeous performance of Zemlinksy’s Die Seejungfrau with the ensemble in 2014. His latest appearance at the podium, heard Thursday night in the Kennedy Center Concert Hall, was another chance to wonder what might have been.

A program completely devoted to 20th-century music was the first thing to admire, beginning with an incisively conducted performance of Britten’s “Four Sea Interludes” from Peter Grimes. Conlon made a point of waiting for the audience to settle into something a little closer to silence before beginning the “Dawn” movement on a limpid violin note suspended in the air.

The orchestra had just returned from a mini-tour to Russia earlier this week, and a sense of fatigue seemed to contribute to an effortful performance. The oozing string sound was fine, especially in the “Moonlight” third movement, but the oboe and flute parts tended toward stridency and constriction in the “Sunday Morning” second movement. Conlon kept the pacing manic and crisp in the “Storm” finale, but while it was all well executed, the overall effect was perfunctory and lacking in color.

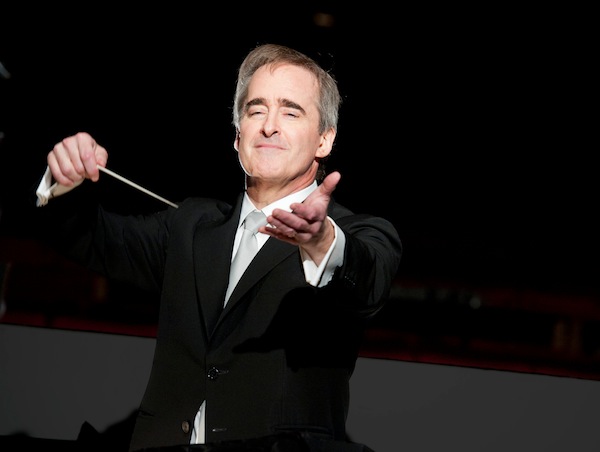

Lise de la Salle

Lise de la Salle made a sensational NSO debut Thursday night playing Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 1, a 15-minute corker of a piece. The French pianist sped off impetuously in the Allegro passages, confident in her impervious technique. Conlon, with nimble gestures, kept the sometimes slow-reacting orchestra in pace. The solo cadenzas were astounding, especially the crushing forte sound at the end of the second section and the virtuosic leaping of registers near the end of the final one.

While the orchestral contributions in the fast outer sections sounded harried, the central slow section provided a beautiful, gloomy contrast. Conlon moved the first and second violins back together on the left, reversing Eschenbach’s accustomed split seating, and placed the glockenspiel player close to the podium, for better coordination with the soloist. For the most part, it worked.

Most of the NSO musicians came home from the tour over the weekend, but some were still in St. Petersburg on Monday when a suicide bomber blew himself up inside a city metro train, killing thirteen people. On behalf of the orchestra, Conlon announced that they would dedicate the performance of Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony to the victims of that attack. The piece was also part of the NSO’s tribute to Rostropovich this year, as it had been for a concert at Carnegie Hall dedicated to their former music director and conducted by Eschenbach in 2013.

Conducting without a score, Conlon led an assured and urgent rendition of this complex work. Violins and violas were lush on their soaring melodies in the first movement, and the martial sections were hammered and ruthless. While Conlon kept the first movement at a moderate tempo, his second movement felt too fast for Allegretto, which was exciting and sharp but breathless. The trio sections, with fine solos from violin and flute, were graceful, and the consistent pacing gave the piece the balletic feel of coordinated dance.

Delicate flute and plaintive oboe solos complemented a luscious, enveloping string sound in the third movement, which Shostakovich marked with the unmistakable qualities of the Russian service for the dead. A rapturous silence descended as people leaned in to listen, and the musicians responded with their most deeply felt playing. The ghostly harp solo that concludes the piece, followed by a whispered major chord, was cut short by the intrusion of the bombastic finale, in which the brass plastered the hall with an immutable wall of sound.

In his remarks before the piece, Conlon first referred to this symphony’s “ambiguous” meaning, and indeed the blistering finale is easily heard either as an optimistic sort of Soviet patriotism or as a critique of blind devotion to the state’s menacing power.

More questionable was Conlon referring to “private testimony” about the hidden meaning of this symphony, repeating the Shostakovich stories by Solomon Volkov in his widely discredited book Testimony. If anything, the piece is more chilling and a more dire condemnation of authoritarianism if it represents Shostakovich knuckling under to Soviet demands.

The program will be repeated 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday. kennedy-center.org; 202-467-4600.

Posted Apr 08, 2017 at 11:28 pm by Tom Bradley

I have never heard the National Symphony play with such brilliance in my life. The strings were ultra lush and the brass was vienna phil. like. Woodwinds, perfection. I wish they sounded like this under Eschenbach. Tom